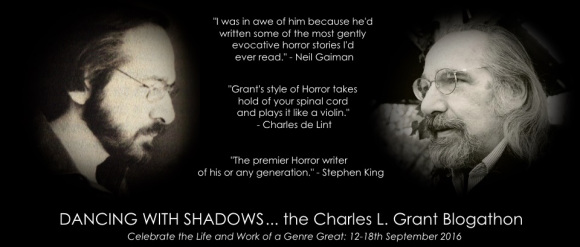

(Neil Snowdon is curating a series of blog posts celebrating the work of the late Charles L. Grant, one of the premier writers and editors of horror fiction. The parent post, with links to other posts, can be found here.)

I didn’t learn to appreciate Charles L. Grant until later in life. I think I first heard of him when my mom bought me a copy of Dark Forces, that foundational anthology of horror fiction edited by Kirby McCauley. Like most folks who read that book, I was excited by a big new story from Stephen King, and I confess to an almost criminal lack of curiosity about the other writers included. Once I was finished with King, though, I alighted on more stories, here and there. I remember being delighted by Edward Gorey (cartoon images in a fiction anthology: I thought that was revolutionary!), I remember enjoying the Ray Bradbury and the Karl Edward Wagner … but Grant’s story, “A Garden of Blackred Roses,” confused and frustrated me.

It started out like a King story. A young father at home with his family, a pleasant winter scene outside, and strange, winter-blooming roses stolen from a creepy house down the road. The death of the family cat quickly followed, and the protagonist experienced a frightening, red-eyed visitation later that night. Eleven-year-old me was all the way on board.

But then the story shifts to another character, a man pushing sixty with an oddly contentious relationship with his wife. Kids frequent the diner he owns, and he chases them away when he thinks they’ve been eavesdropping on adults around the neighborhood, and recording their pre-coital conversations. The story shifts perspectives twice more, and ends on a note that went straight over my head.

As I grew older, I gravitated more toward the four-color, blood-splashed spectacles of horror fiction: Clive Barker’s Books of Blood, John Skipp and Craig Spector’s The Light at the End and The Scream … I didn’t have patience for what people were starting to call “quiet horror.” I had no ideological aversion to it; it’s just that I was a teenage boy in the 80s – my mind was moving at a different speed.

It wasn’t until many years later, after leaving horror behind altogether, and eventually coming back to it with a new way of understanding the world, that I rediscovered Charles L. Grant. This time, I was better prepared to appreciate him. I picked up Scream Quietly, the huge retrospective collection of Grant’s short stories, edited by Stephen Jones, and meandered slowly through the table of contents, skipping around at whim.

It wasn’t until many years later, after leaving horror behind altogether, and eventually coming back to it with a new way of understanding the world, that I rediscovered Charles L. Grant. This time, I was better prepared to appreciate him. I picked up Scream Quietly, the huge retrospective collection of Grant’s short stories, edited by Stephen Jones, and meandered slowly through the table of contents, skipping around at whim.

My experience, of course, was entirely different. Here I found a writer with a talent for elegant prose, an instinct to recognize the beauty in horror (something dear to my own heart), and a nuanced sensitivity to the million minor catastrophes of the human experience.

I’d forgotten the title of the story I’d read all those years ago, but I recognized it soon enough, once I started reading it. It won’t come as a surprise to you to learn that “A Garden of Blackred Roses” is now one of my favorite Grant stories. It boldly eschews conventional narrative as it leaps from one perspective to another, each providing a different window onto the strange horror which resides in the middle of this small Northern town in a nest of curated beauty. The story turns its focus on love, in both the young and the old, and on the varieties and consequences of longing. Grant references Nathaniel Hawthorne’s The Scarlet Letter explicitly, and W.W. Jacobs’s “The Monkey’s Paw” more subtly. It’s a lovely, understated, powerful story — and, lest you be fooled by all this talk of “quiet horror” whenever Grant’s name comes up, it’s important to note that it leaves one of the characters at the point of shocking violence, before coyly leading the reader to another scene. One shouldn’t mistake quiet for gentle.

I’m happy I’ve come back to Grant, mature enough now to understand what he’s telling me. And after all, there are still the ghouls, the ghosts, the little people under the earth, and the gods from adjacent worlds to populate all these stories, and give the kid in me the comic book thrills he still craves. Charles L. Grant was indisputably one of the great writers of the horror genre, a celebration of its potential and a repudiation of its detractors, and I await the day some enterprising publisher brings him back into print, beyond the occasional expensive, collectible edition. Until that time, seek him out, like some lost and rumored country, and come back home with strange secrets to tell.